The masses have sat through the best part of a chapter (at least) absorbing everything that we've talked about. But they're a little rowdy because we've been talking about programming languages without actually doing any programming. Well, that's completely understandable! I would be just as annoyed if I wasn't the one writing the book. I know what's coming but they don't.

OK, let's try appeasing the masses. Here's some code:

"Hello, World!"The masses are silent. Their stares harden. Their spokesman — who they've nominated while I thought of this snippet — says (while systematically tearing down the fourth wall): "That's just a bunch of quoted words! Just like this one that I'm speaking."

The crowd agrees.

Ok, you're right. It is some quoted words, but they're quoted words that both humans and computers can understand. That's pretty cool. Well, I thought so, at least.

The crowd of humans arrayed before us know the words and that the words have meaning behind them and form an understandable sentence. The computer knows only the individual letters or symbols in the words, and cares not that the words have a meaning or that the words form an understandable sentence. "Those things are only important to the humans", it thinks, without acknowledging the Machine Learning zeitgeist that has sprung up recently.

When we say the sentence to the masses, they can easily repeat it back to us. To speak to the computer, we need to open up a prompt for the particular language we want to use to converse. Different languages have different prompts. We can't just speak to the computer to program it. Not yet, anyway.

On the first line of Elixir code here, we're giving the computer an instruction that looks like a regular sentence. This is because it is a regular sentence. In computer-nerd-terminology, we refer to this double-quoted collection of symbols as a string. It's easier to think of it like a string if you think of all of the sentence's parts being connected by an actual string:

The computer then takes in this string, interprets it and tells us how it interpreted the string. In this case, the computer is just parroting our sentence/string back to us. The computer can do a lot more than this, believe me. Computers wouldn't be very good if all they did was parrot back to us.

The masses are now getting fidgety. So far we've shown just the one line of code. Twice, yes, but it's still just one line of code. And the computer is prompting us with this line.

Ok, so the computer can parrot things. But what else can it do? How about we ask the computer to do some simple mathematics?

2 + 43 - 64 * 123451234 / 4 + 2 - 12 * 3This appeases the masses, slightly. They're a fickle bunch. The computer is now no longer parroting things back to us. It's instead calculating the not-so-advanced mathematical equations we're giving it, and then giving us the right numbers. If you're not convinced these are the right numbers, I would encourage you to get a pen and paper and to puzzle them out yourselves. You'll find out that the computer is right. Good computer!

The masses realise that Elixir is now built for more things than simple parroting. Elixir can do calculations too! We've used the symbols +, -, *, and / here, asking the computer to add, subtract, multiply and divide, in that order. You might think to use x to multiply, but that has a different meaning as we'll see later on. You should use * when you wish to multiply things, as that is what Elixir expects you to do.

We've now seen that Elixir can handle words and numbers easily. But what else can it do? Well, it can remember things.

sentence = "A really long and complex sentence we'd rather not repeat."

score = 2 / 5 * 100

x = "not for multiplication"At any point in time, we can ask it what sentence or score or x is and it will tell us:

sentencescorexsentence, score and x here are variables, and they're given that particular name because the thing that the computer remembers with that name of sentence or score or x can vary. Remember when we talked about multiplying numbers and we saw that we couldn't use x to multiply? The reason for this is because Elixir would read x as a variable, not as a suggestion to multiply the numbers on either side. So we will continue using * instead whenever we wish to multiply two numbers.

We can tell the computer to replace its definition of a variable with another one. This is often referred to as re-assignment. Let's replace (or re-assign) the sentence variable's definition:

sentence =

"An even longer and significantly more complex sentence that we might be ok with repeating, if the mood takes us."Then when we ask the computer what sentence is, it will have forgotten the old sentence and will only know the new one.

sentenceNow the masses are looking chirpier. Some are even smiling! Isn't that wonderful? Let's create another variable called place:

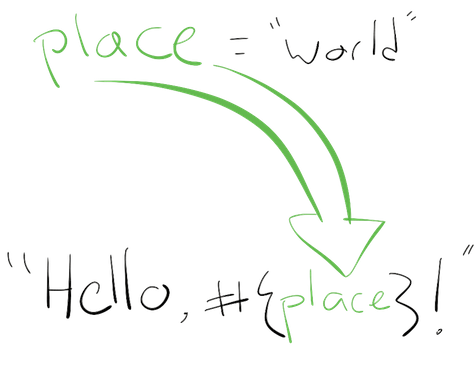

place = "World"The computer will now remember that place is "World". "But what's the use of just setting a variable like this? Why make the computer remember at all?", Isodora (the spokesperson) says. By the way, we have since learned the spokesperson's name is Isodora, and so we've done some variable creation of our own in our own brain: spokesperson = "Isodora". Woah. "Just call me Izzy", says Izzy. Ok, we will -- making our brains reassign the spokesperson variable: spokesperson = "Izzy".

"Hello, #{place}!"The masses go nuts. It's pandemonium! Then after a few shushing motions with my hands (which are completely ineffectual) and a quick "OI!" from Izzy, they're (mostly) quiet again.

"What just happened?", asks Izzy? But you, Dear Reader, had asked that question already. Izzy didn't hear because of the crowd and the sheer, unbounded pandemonium.

What on earth are those funky characters around place? You can think of them as a placeholder. Nerdier-types would call it interpolation. It tells the computer that we want to put the place variable riiiiight here, right after Hello and the space, and right before !.

The computer takes the sentence that we give it, realizes that there's that funky #{} placeholder indicator, and it remembers what place was and puts it right there. Pretty nifty, eh?

The number of seconds in a single day is below. Use this code block to calculate how many hours there are in 30 days.

seconds = 86400